If skydiving is a strange game of reverse-dodgeball (throw yourself at the dirt ball and try to just miss), then speed skydiving is the upper end of the game. As the fastest sport on Earth, at no other time will the “ball” be coming at you that fast! For neither the faint of heart nor the inexperienced, it is a game of intense mental preparation, alertness and mind-over-body control that can test the mettle of a skydiver with thousands of jumps.

If skydiving is a strange game of reverse-dodgeball (throw yourself at the dirt ball and try to just miss), then speed skydiving is the upper end of the game. As the fastest sport on Earth, at no other time will the “ball” be coming at you that fast! For neither the faint of heart nor the inexperienced, it is a game of intense mental preparation, alertness and mind-over-body control that can test the mettle of a skydiver with thousands of jumps.

The goal of the speed skydiving event is to turn in the highest average vertical speed through a designated one-kilometer course from 8858 ft to 5557 ft (1000 m). The current world record for speed skydiving is 511 km/h (317.5 mph) That’s almost three times normal belly-fly speeds!

Prerequisites

While there are currently no formal requirements for speed skydiving, I would recommend the following: C license (minimum), 1000 jumps, thorough knowledge of how the gear works (and fails), the ability to hold heading in a head-down orientation, the ability to easily handle off-landings, and good reflexes.

Before You Start: Gear Check

Before you begin to train for speed skydiving, go through your gear with a fine-toothed comb with an eye to making it ultra-freefly friendly. Make no mistake, a premature opening can kill you at these speeds. And your gear has never been tested in this scenario. The manufacturers will tell you that you are going where angels fear to tread.

Velcro is an active enemy in this environment. Take a close look at your gear and ensure that maintenance is two or three steps above adequate. Closing loops should be tight. All tuck tabs and flaps should hold their intended position easily, with little to no tension. Riser covers in particular should be well-seated. Magnetic riser covers have been used, but they are not currently recommended. The pilot chute pud should be in good shape and rest comfortably close to the container. Under no circumstances should you “bury” the pud inside the pocket. All retaining bands should be in good shape. Failing to use a leg strap retaining band may not cause a major issue, but it will hurt.

Don’t stop with the rig! Also have a close look at your helmet visor for general condition and security of the visor. If a visor comes off at 300 mph, it is a potentially sharp object about to travel the length of your body at high velocity. Afterwards, you get to experience skydiving blind, which is never recommended.

Also choose clothing that is tight and tough. Flapping clothing can and will tear in the force of a 300-mph relative wind.

Audible altimeters (notice the plural) are mandatory. The rules require at least one for safety. The other is to give you key vertical location information like that start of the course, or (more importantly) the bottom of the course. I prefer to set mine just a bit above the bottom of the course and let reaction time handle the difference. I also intentionally set my altitudes 500 feet higher than normal. You should also consider the higher wind noise in the helmet at these speeds, and get that helmet tight!

In order to prove the speed of your training and competition skydives, you have to be able to accurately measure your velocity. The current international standard requires the use of two L&B ProTracks attached in line with the laterals of your rig. Some competitors are using Lycra pockets sewn to the sidewalls of their main container. A single ProTrack (or similar device) mounted in/on the helmet is not as accurate.

When measuring your speed, there are two things you must keep in mind. First, this event is NOT based on PEAK speed. If your wrist-mounted altimeter says you did a max speed of 284 mph, you are probably running slow. The event is based on average speed in the course, as measured on two devices. Secondly, know that a difference in measurements between the two devices can have a HUGE impact on your actual score (see rules about Out-of-Bounds). You also have to make sure that your devices are set to measure properly. On L&B products (I am not sure about others), you should be set to read TAS (True Airspeed), rather than SAS (Skydiver Airspeed). The latter adjusts for pressure and is totally invalid for this event, but it is the far more common setting.

Airspace Concerns

When you manifest for a load, consider what else is on board. Complicated airspace is a bad idea. The fact is that your mass plus your velocity on a speed skydive make you a true meat missile to other skydivers if you end up in their airspace. Don’t hesitate to scratch from the load if there are lots of different types of skydives going on! Complex jump runs make it very hard to have confidence that people will be where you expect them, and this is critical. At the speeds you want to attain, you can’t see and avoid other jumpers in time. You just have to plan to stay clear and stick to that plan.

I prefer to be out first, and just a bit short. This means that I will sometimes land off the DZ. But that is better than risking a collision. Conventional practices for loading put fast fallers out later because of reduced drift, but a speed skydiver is going so fast that you can quickly pass other skydivers/groups vertically, then slide under them if you’re not falling straight down or during your deceleration flare. Seek advice from the local S&TA and load organizers, and coordinate every speed skydive with them.

Anatomy of a speed skydive

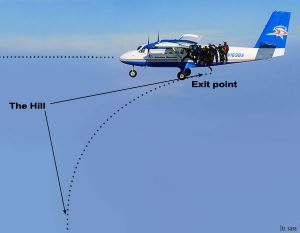

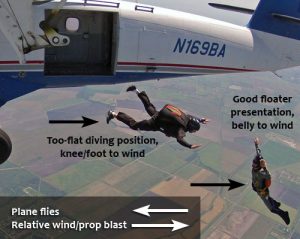

A normal speed run starts with a head-down exit at 13,000 feet (12,500ft is fine for practice); head-down is the fastest orientation possible. The key to a good run is acceleration, acceleration, acceleration. And this is just the first section of the skydive! On exit, focus on building speed. Getting “off the hill” takes on new meaning, as “the hill” is going to get longer because maximum velocity is much higher than usual.

The key ingredient to the bulk of the skydive is to stay relaxed. Be Zen. If you are tense, you will feel oscillation develop like a student potato-chipping. As you tense up to control the oscillations, they will get worse. If you thought your AFF-I’s were insistent about relaxing, you ain’t seen nuthin’ yet. Think of this oscillation as potato-chipping in a vertical axis. Here is the catch: Your body has to stay relaxed, while your mind is at peak awareness. You have to learn how the air feels at these speeds. If you feel something out of the ordinary (like a main flap opening and slapping against the container) you have to react right now! As you learn how the air feels, you may react to nothing a time or three, but you will figure it out.

The other reason to stay sharp is that when you come to the bottom of the course, you have less than 10 seconds to slow down to less than 150 mph for deployment. From experience, I can tell you that you will feel each and every mile per hour you are over 135-140 as a slap in the crotch and the neck. Opening at 160 mph is on my “do not do that again” list. While you are doing this, you will need to check your heading and set up for the end of the skydive to take you away from the line of flight.

At the bottom end, your focus goes from “go faster” to “slow the hell down!” First, check your heading and face across the line of flight. As you slow down, you won’t continue to fall straight down. You’ll take that high vertical speed you’ve generated and shift into a fast-fall track to begin bleeding off speed, and this will create very fast horizontal movement. Horizontal speed of 70-100 mph is not impossible after a fast speed run, and this can absolutely put you into other groups’ airspace if you move up or down jump run. I do not recommend immediately flattening to your belly and getting big as a winning strategy. From 250+ mph, that just hurts. Shoulder and finger dislocations are possible. Shift first to a fast-fall tracking position with your shoulders rolled back, then bring your head and shoulders up into a head-high tracking position. Then bring your arms and hands out slowly until you are falling slow enough to fully extend them. Then pour your entire being into maximum deceleration! If you don’t work hard enough at this, you may rest assured that the opening will provide you with instant feedback about your lack of technique. Once the main is open, take the time to actually inspect it, as openings at too-fast speeds can break your parachute.

Now that you are under canopy, check your location over the ground. It is very possible that you are not in a normal opening location. Decide if you can make it back to the DZ quickly. But do NOT fly directly up the line of flight. EVER! If you exited first, you are possibly under the jump run. If you exited last, you almost guaranteed to be under the jump run. As you check airspace, LOOK UP!!! Having freefall jumpers come past you is most definitely in the category of “undesirable.”

Performance Logging

If you want to get better, you are going to have to log. Not the usual stuff, either. Get both ProTracks out and compare the data. Determine if you have gone “out of bounds” (see the rules). Take the time to think over your body position very carefully and in minute detail. Focus on eliminating anything that can cause excess aerodynamic drag. If you had oscillations, it is time for long talk with yourself. You will find yourself spending real time poring over your acceleration curve and trying to figure out how to improve it.

More Info

You can find other good information at www.speed-skydiving.com.

Have fun!

As you pour time, energy, and money into this, remember the idea is to have fun! The main competition in this event is actually with yourself–mastering your body and mind. Triumph will bring you in to the ranks of humans who have gone faster without a vehicle than most will ever go in a vehicle!