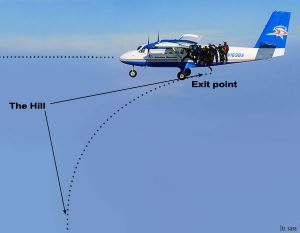

You’ve probably heard skydivers talk about the “hill” and “flying the hill” when discussing exits from powered aircraft flying horizontally. If you’re unfamiliar with the term, let’s define it! The hill is that transition period between your leaving the aircraft and reaching terminal vertical velocity. When you exit, you are initially traveling horizontally just like the aircraft from which you exited. Gravity works quickly to accelerate you towards the planet, however, and your horizontal velocity quickly decelerates (due to wind resistance) to zero relative to the air mass through which you fall.

While you are on the hill (in that transitional state), there are two reasons why flying there is different from flying at terminal velocity. The first is that due to your initially horizontal movement, airflow over your body isn’t coming from below–it’s coming from the front of the aircraft, 90 degrees to the ground (we call this the relative wind and it comes from the direction the aircraft is moving towards). So if you’re thinking of freefall as something you only do relative to the ground or the horizon, your thinking is 90 degrees wrong as you leave the plane and funnels/unintentional flips often occur. Only when you reach terminal velocity are you correct. Think of freefall and flying as something you do relative to where the wind is coming from, and you’ll be right all the time. 🙂

The second reason why the hill is tough is that initially, you don’t have quite as much airflow over your body as you will at terminal velocity. The plane is usually going a little slower than belly-down freefall speeds (the differential is much bigger for freefly speeds). So any inputs you give (legs out, dipping a knee, etc.) won’t seem to do quite as much until you reach terminal velocity. You might hear skydivers say things like “the hill is mushy” when talking about how this feels.

Learning to fly well on the hill is quite challenging for one simple reason: You get so little time to practice it! You only get about 10 seconds of hill time before you reach terminal velocity at standard belly speeds. So while you get little enough time to practice freefall as it is (maybe 60 seconds depending on your exit and deployment altitudes), only a small fraction of that already short time is spent on the hill. It’s a challenge within an already big challenge!

So let’s look at some hill flying concepts to get started on meeting that challenge! For this article, we’ll focus everything on belly-fly exits and assume we are exiting from a left-side door aircraft such as a Twin Otter or Caravan.

Presentation

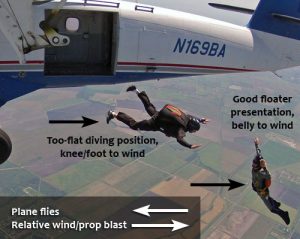

Proper presentation of your body to the relative wind is key to the success of any exit, solo or linked. Good hill flying starts with good presentation; you want to be oriented to the relative wind (forward towards the nose of the plane) exactly the way you eventually want to be oriented to the ground. If you are doing a poised floater exit, for example, you’ll step off the plane with your head up to the sky, knees below, and belly forward towards the prop, perpendicular to the ground. If you change nothing about your body position, you’ll gradually transition to a stable belly-to-earth orientation with your head pointed the same direction the plane was traveling.

When a skydiver unintentionally flips, flops, and flails on exit, the reason is almost always poor presentation. Usually the problem is that the skydiver exits with a literal belly-to-earth orientation, but this means he/she is presenting his/her side or feet/knees to the relative wind coming from the prop. There’s a reason we don’t teach students to fly on their sides–it’s hard! It’s kind of like trying to balance a knife on a table by its blade instead of just laying it flat.

When floaters flail, the problem is usually that they did not get their left sides up and away from the plane quickly enough to present their bellies/chests to the relative wind, so they are essentially flying with their left sides into the wind. To help avoid this, turn your body to stand in the door with your left side slightly further from the plane than your right side; this will get some wind on your chest and belly. Consider standing just on your right foot and trailing your left foot away from the plane a little to get your hips even more squarely into the wind. Now you’re ready for success! On exit, step strongly away from the plane, leading with your left side and keeping your chest and belly into the wind.

When divers flail, usually they are diving out with a belly-to-earth mindset, which presents their right sides to the relative wind. To get your belly into the wind as a diver, you have to have the right side of your body higher than your left. That means launching off your left foot with your body twisted a little to raise your right hip and get wind on the front of your pelvis and belly, and raising your right shoulder/arm/elbow to get wind on the front of your chest.

When belly flying, put the front of your hips/pelvis into the relative wind wherever it may be (depending on the aircraft), and the rest of you will usually follow! Visualize this before your jump; this helps performance significantly.

It’s All Relative

Now that we know how to exit in a stable position from inside and outside the plane, let’s think about staying close to others on the hill. So we can, you know, turn points and stuff. 🙂 This is where things get familiar (yay!), because the physics of staying relative to other skydivers don’t change on the hill. The challenge of staying relative is slightly one of physics because of the lower airspeed we mentioned earlier, but it’s mostly one of perspective.

Mostly, we just have to remember that while we are on the hill, we should throw the horizon and ground out the window, because they are fixed references in a changing world. Don’t try to keep up with the changes by counting seconds out the door, especially since early floaters/divers will have different times out the door. Instead, look at where you are relative to where you want to go and put your mind into hyperdrive.

Lock onto your target like a fighter pilot and see what needs to happen. See that the distance may be increasing between you and your target in terms of altitude, or lateral distance, and catch that before those inches or feet of separation become tens of yards or hundreds of feet. See that you are just a little low or high relative to your target, and fix the levels before you have to perform hero moves to get there. It’s very common for new skydivers to just lock down a body position out the door and try to survive the exit so they can make it to freefall, but the hill is a fun, fluid place to fly because it’s even more of a challenge than terminal velocity.

Caveat: Never, in any skydive, lock onto a target so hard that you forget what else is around, because lack of awareness of others around you can lead to other problems. Lock on in the sense that that’s where you’re going and you’re tuned in to what you need to do to get there, but always, ALWAYS maintain situational awareness.

A great friend and teammate of mine loves a quote that’s really appropriate here: “You can only make a hero play when you’re out of position.” The key to flying relative to others on the hill is to see quickly when your position is worsening and fix it before it takes a hero to get back. Awareness guides skill, and both come with experience.

Competition Perspective

When doing 10-way speed years ago, then as now it’s all about the exit and hill flying. The best teams are building 10-ways from a no-show (all-divers) exit in 10 seconds or less, and on the best jumps in 8 seconds or less. Our team captain (Roger Nelson, founder of Skydive Chicago and a super awesome 10-way competitor) would tell us that if you look at your target (assuming that your target is stable!) and see backpacks, you’re a diver. If you see bellies, you’re a floater.

This gives you an idea of the body positions you need to get into to reach your target. See your target, see what you have to do relative to the target, feel the wind on your body, and use it to fly where you want to go. It sounds simple, but we all know it isn’t! 😉 Start with good presentation that puts you on the same plane as your target, follow that with awareness of what needs to be done, and close the gap with the techniques you’ve already learned to get closer to your target.

You might have noticed that we have spent no time on actual skills of body flight, such as legs out to go forward, sideslide technique, etc. Why? Well, those skills are all the same on the hill as they are at terminal; the physics don’t change. What changes on the hill is just your perspective relative to the horizon; it’s all a head game. As a licensed jumper, you have already demonstrated that you know what it takes to go forward, back, up, and down relative to a target. So take that knowledge and apply good presentation and quick-thinking awareness to it, and you’re a hill-flying rockstar. 🙂